The annual climate summit, after a year of Corona postponement, is happening in Glasgow as CoP26, the first two weeks of November. I will attend the CoP for Climate Neutral Group. And I give hereby my six tips for the summit summarized in a few words: you get more ambition with more flexibility. My tips and tops: use the CO2 market, make use of negative emissions and commit to a specific methane reduction target and a national temperature reduction targets.

1. Ambition is essential

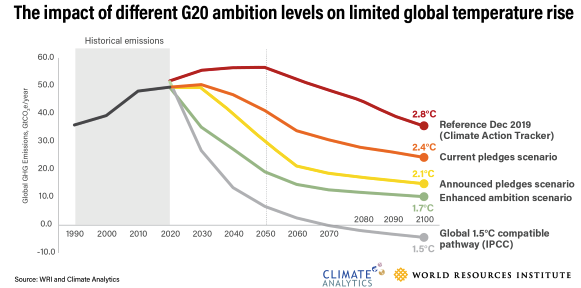

This summit is the world’s last chance to get back ‘on track’ with the 1.5° C scenario. Progress has already been made. While the climate plans prior to the Paris Agreement led to a 3-4°C temperature rise, the current 144 tightened plans are already reaching 2.4°C. So there is still a gap. And one degree difference can just lead to heavier rains and scorching heat and drought.

More ambition with more flexibility to get there on time

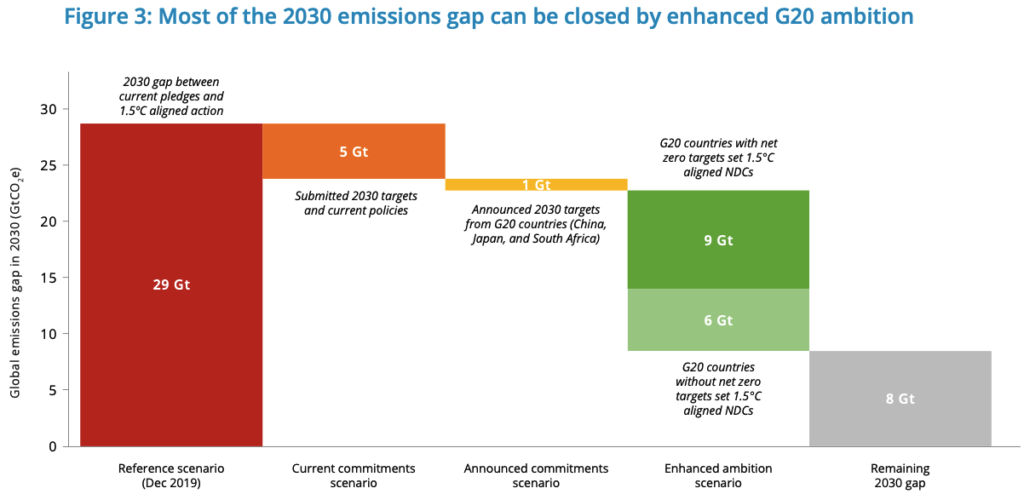

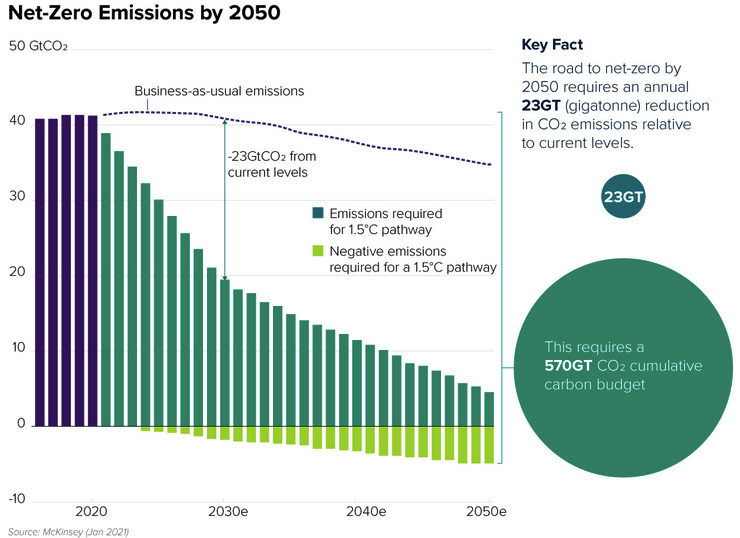

In particular, G20 countries that still have to submit a tightened climate plan are China, India, Turkey, Australia, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil, which together cause more than a third of global emissions. China and India recently made announcements. And Saudi Arabia last week committed to net-zero by 2060. If all G20 countries do indeed agree on more ambitious 2030 targets and also achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, this will limit warming to a 1.7°C increase and 1.5°C is within reach!

I note three conditions to target setting:

- Joint implementation and cooperation on CO2 targets work! This also works through the EU, which makes use of European cooperation in the field of energy and CO2 trade. Collectively, the EU is already in 2020 at -23% compared to 1990, more than obligated was, and the European Climate Act contains a target of -55% in 2030 and climate neutral in 2050 and negative thereafter.

- Make room for ‘over-compliance’. It is becoming increasingly difficult for governments to legally commit themselves to hard CO2 targets for an entire economy in a plan or at a climate summit. It is also sometimes difficult to establish a long term national budget for this. I think it is better to leave room for additional reductions by a country and by sectors, than for countries to make strict agreements and then not meet them, while you cannot enforce them internationally. It is important to monitor progress closely. That is also on the agenda of the top: requirements for transparent reporting.

- Beware of setting technical absolute targets as a country such as phasing out in a certain year the use of gas coal and oil. It is not without reason that the IPCC talks about reducing ‘unabated’ fossil fuels. With measures such as CCS, CCUSE, CTBO, the climate impact of gas and oil can be abated. We see that an ‘getting-off-the gas’ goal can have undesirable effects such as loss of security of supply, increased costs for consumers and SMEs and burning more coal as we see in the EU at the moment. But absolute targets on the use hydrogen or building with wood are also risky: It creates new monopoly countries and dependency. The fact that banks and pension funds no longer finance fossil investments is a good thing. But governments should limit themselves to carbon targets and not choose or exclude a certain technology or fuel.

2. Use ‘negative’ emissions for extra ambition

The EU has agreed in the Climate Act that emissions must be negative after 2050. Technical negative emission projects are often thought of, such as Direct Air Capture (DAC) or the storage of CO2 in basalt, olivine weathering or in biochar, the residual product of pyrolysis. However, these are often very expensive (sometimes more than 200 euros per tonne of CO2) and barely available. So to build policy on this is very uncertain. It is better to also make use of available ‘nature-based carbon removals’. This is possible with carbon sequestration in forestry and agriculture, but also with hemp and elephant grass. But also in a wet environments via to the expansion of salt marshes, sea grass, mangrove and seaweed and kelp.

Because the scope for this is not also infinite, use can also be made of the global CO2 market. Hence, if a country or company finances more reductions elsewhere than it has itself in CO2 emissions, you can also see this as negative emissions (see below).

3. Use the Global CO2 market and reductions in international supply chains for extra ambition

Researchers from the Dutch researchers, PBL called on the North to achieve net-zero by 2040, because developing countries need more time. Developing countries themselves also indicated that we must not expect net-zero in 2050 from them. I propose therefore, that those reductions be made earlier then, in particular, via the global CO2 market. Companies can also reduce the international carbon footprint of their supply chain, for example by making coffee and cocoa production more sustainable and by combating forest clearing. With this, the North finances also reductions in the South. An additional advantage is that twice as much can be reduced for the same money via the CO2 market and that additional development is also initiated in those countries.

The study of the University of Maryland and IETA shows carbon trading potential to help nations meet net-zero by 2050. The variation in marginal costs offers potential gains with Article 6 trade. Potential ‘ITMO’ transfers are 1.7 GtCO2 in 2050 at $1 trln/a. It will be 3,7Gt in 2030 at $ 300 bln.

At the Climate Summit, agreements will have to be made about how countries can transfer emission reductions to each other. Article 6 of the Paris Agreement offers that possibility. Switzerland, Sweden, South Korea and Japan are already undertaking emissions trading pilots with developing countries.

4. Use the voluntary carbon market to help achieve national targets

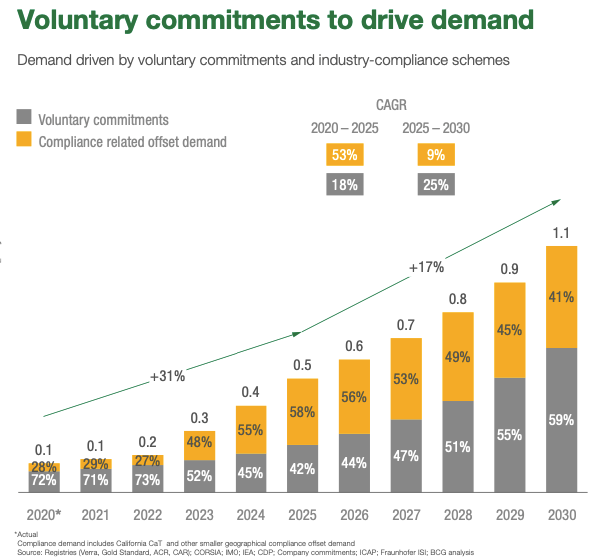

In a calculations by Shell and the Boston Consulting Group, they estimated that the global CO2 market from 100 Mton now, may increase tenfold by 2030 to 1.1 Gigaton. Less than half is via the mandatory CO2 market in order to meet CO2 o (see above). But more than half is via the voluntary CO2 market. This concerns, for example, a Dutch insurance company that wants to compensate the latest emissions from, for example, commuter traffic or heating by buying carbon credits from CO2 reduction through cookstoves in Ethiopia or forest protection in Peru. These reductions also help those (host) countries achieve their own NDC CO2 targets. Because the emissions of that company will remain in the Dutch report.

The voluntary CO2 market can also be used to meet help domestic targets. The Dutch voluntary CO2 carbon market does that with domestic projects; for example, by rewetting Frisian peat meadows or planting forests via the Dutch National CO2 Market Foundation. The same time, should the voluntary CO2 market not be an excuse for companies to omit their own reductions. For example, the Climate Neutral Certificate of the Climate Neutral Group requires an annual CO2 reduction of about 5% in the first few years to absolute zero 2050, and only the remaining CO2 emissions may be compensated elsewhere.

5.Advocate National Temperature Reduction Target (Cooling Target)

Countries now have CO2 reduction targets, but the real goal is of course to combat global warming. Now it could possible to take concrete measures to lower the average national temperature by:

- the ‘albedo’ effect by whitening surfaces, so that the heat reflects and is not absorbed;

- greening: more green cools down. Particularly in cities with measures such as laying less stones and asphalt, but more open earth with permanent greenery, trees, even ‘tiny forests’ and green roofs and facade vegetation in cities and;

- water surfaces that also cool the air.

People are also thinking about ‘geo-engineering’ projects, in which, for example, sulfur particles are being spread in the air or ocean or clouds are made whiter to cool the earth. However, people are afraid of possible negative effects and air pollution that this could entail. Incidentally, I came across a natural form of geo-engineering in Merlin Sheldrake’s book ‘Entangled Life’ about fungi. Forests appear to be able to shoot masses of spores high into the air to create rain clouds in the atmosphere if the soil becomes too dry. Perhaps such natural geo-engineerig would be acceptable; but can this be done on a large scale?

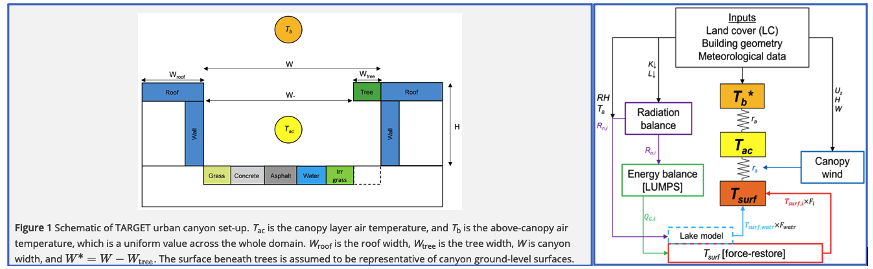

At the urban level, the albedo effect is used by urban planners with Green-Blue-Infrastructure (GBI) and they use models to calculate the temperature reduction. In many countries there are urban GBI initiatives for biodiversity and a healthy living environment. This brings back the average temperature in a country. Replacing tiles with vegetation can reduce the local temperature by 0.4°-0.6°C. Trees in a street can reduce the temperature by 4.5°C. So why not make that part of national agreements? Countries could make an agreement in their Climate Plan to effectively reduce the average temperature in their country by x° Celsius.

6. Agree rapid methane reduction for cooling

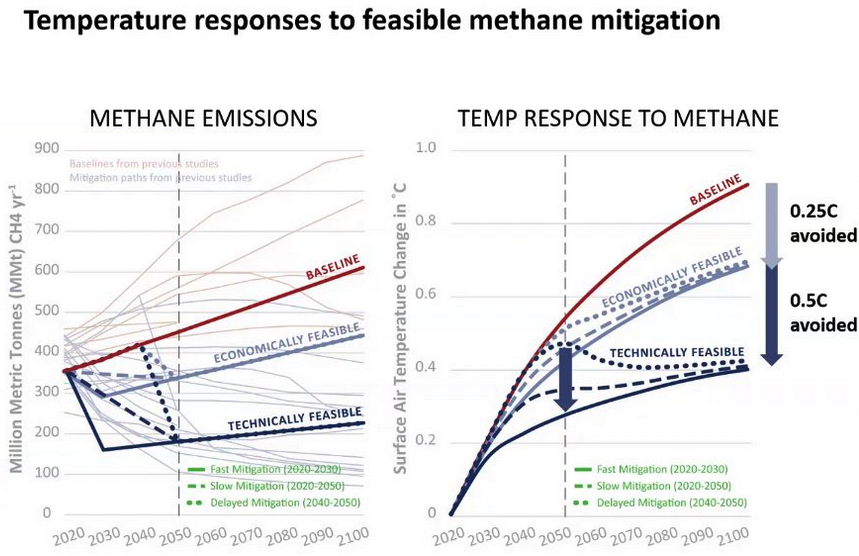

Dutch newspaper Telegraaf recently cheerfully headlined that the farmer should be left alone because methane does not contribute to more warming. The reason was a study by Miyes Allen et al. that indicated that methane is broken down in the atmosphere after ten years and that an existing livestock does NOT contribute EXTRA to warming. However, the methane in the atmosphere has already contributed to the current warming. Current climate policy uses CO2 equivalents and compares the ‘global warming potential’ (GWP) of non-CO2 emissions with that of CO2, calculated over a lifetime in the atmosphere of 100 years. Because the methane gives 28x as much effect as CO2, but is converted into CO2 sooner, that extra effect is actually about 80 times more powerful in that short time. In their latest report, the IPCC argues in favor of reducing methane as quickly as possible, because this immediately counteracts further warming.

The US and EU have therefore called on 25 countries to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030. This could further limit warming by 0.2°-0.5° C in 2050. That also shows Environmental Defense Fund (see below). Last week, the European Parliament also called for binding agreements on methane reduction. And this concerns methane from the oil and gas sector and the waste sector as well as livestock farming. Dairy companies such as Friesland Campina and Arla are already conducting pilots with feed supplements to reduce enteric methane from dairy cattle: this maybe lead to 15-30% less methane.

In my tips for the climate summit, I argue to make more use of the flexibility that is permitted in the Paris Agreement: the CO2 market, the negative emissions, the methane reduction and the temperature reduction targets. This means that a higher ambition can be achieved and the CO2 targets are achieved sooner.