In the past year, a lot of attention has been paid to the role of international supply chains. This was because we noticed their vulnerability due to corona as important manufacturing parts could not be delivered, shareholders are forcing oil companies to reduce CO2 emissions in the upstream and downstream chain (‘scope-3’ emissions) and research showed that the EU is one of the largest importers of raw materials that cause tropical deforestation. So there is an opportunity to look at the resilience of the supply chain and at the embedded carbon in the supply chain.

Especially now EU must decide how to meet the tightened CO2 target, it is important to make use of the flexibility allowed in the Paris Agreement to make more ambitious CO2 targets feasible and affordable. Companies can do this by realizing part of the extra CO2 reductions in their international supply chains. Another advantage of this approach is that you also tackle global emissions in countries where this would otherwise not be high on the agenda yet or would be too expensive without financial support. Most developing countries, in their climate plans (‘NDCs)’, invite Northern countries to finance CO2 reductions in their country, hence by using the global carbon market.

Industry still a long way from being CO2 neutral

While the energy sector could be CO2 neutral around 2030, this is not yet possible for industry. In July, the European Commission will present proposals for the ETS to contribute to the EU’s 55% target. The ETS budget is now -43% compared to 2005. That could go to 50% for example or least to decrease the overall ETS budget faster.

It is therefore understandable that the industry, in addition to investing in hydrogen and CO2 storage (CCS) and reuse (CCUSE), is looking for additional opportunities in the chain.

Especially high emissions in consumer-oriented sectors

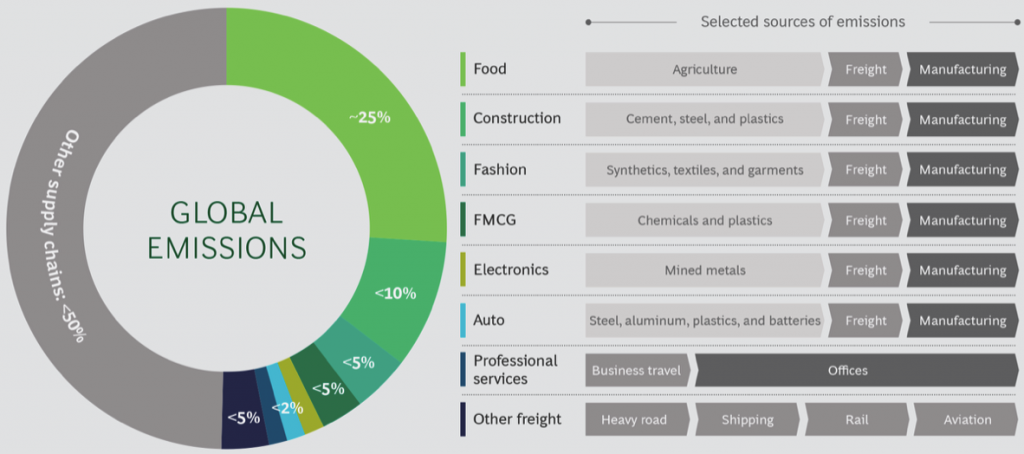

Moreover, especially from companies in consumer-oriented sectors, emissions in the supply chain are much higher than the direct emissions from their own activities. Eight international chains are responsible for more than 50% of the annual greenhouse gas emissions, according to the Boston Consulting Group: food, building materials, clothing, electronics, cars, consumer goods such as cosmetics, services and other imports of products. Most of the emissions in that chain come from mining, basic materials, agriculture and transport.

Large reduction potential in international supply chains

Guidehouse for example said decarbonized supply chains is local supply chains. However, the potential of the reductions by tackling the chains themselves is big: 50% of global greenhouse gas emissions according to BCG. By setting a net-zero supply chain target, companies can reduce their climate impact, enable emission reductions in sectors that are difficult to mitigate, and accelerate climate action in countries where this would otherwise not be high on the agenda.

There is to date small interest in the EU in reducing the international footprint in the EU. There was no attention whatsoever for the international CO2 market, only Switzerland, Sweden, Norway and Canada are interested in this potential.

Costs are low in most supply chains: a CO2-free chain in the medium term will only cost end consumers 1 to 4% more. Example: less than $ 1 for $ 40 jeans; $ 4 extra for electronics and $ 600 extra for a car.

In what ways can chain reductions be involved in climate policy?

- Voluntary CO2 market. Numerous multinationals, from Microsoft to Google, Booking.com and Bayer, have voluntarily agreed on CO2 targets. They want to achieve this by, in addition to their own reductions, buying carbon credits for forest protection, sustainable energy and sustainable transport. They thus compensate for the latest emissions. They may find them in the international supply chains.

- Climate Neutral Certified Products: companies in the food or non-food sector that want to sell their product in a climate neutral certified via Climate Neutral Group – in process of ISEAL approval – must reduce the emissions of the product in the entire chain by 25% by 2030. They can do this by financing reductions in their chain in various ways. Think of financing intervention from shadow trees on coffee and cocoa farms, to carbon sequestration in agriculture, transportation on biofuels to supplements that reduce methane of cattle. The realised reductions can be subtracted from the total carbon footprint accordingly: this is called ‘insetting’.

- Under the Paris Agreement, countries are allowed to achieve part of the reduction targets by purchasing CO2 reductions from other countries (so-called “Art 6 mechanism “): Switzerland, Norway, Sweden and Canada are making preparations for this. Agora advises Germany to make use of this now that it must tighten its CO2 target from the courts. Member States could partly use this to help meet their tightened CO2 targets.

- Linking the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) with other ETS systems or linking the ETS to the carbon credits of the Paris Accord. The largest party in the European Parliament – European Peoples Party (EPP) – had proposed this for the European Climate Law last year. There was still too little support for it. I expect that the European Commission will investigate this anyway, as soon as countries make agreements about Article 6 at the Climate Summit in Glasgow in November. Companies can then partially, say 10%, with CO2 rights comply with the ETS.

- Changing the CO2 accounting of countries from being responsible for your own emissions in your own country, the ‘production’, to the emissions that were needed for your total ‘consumption’: then you also must pay for the CO2 emissions of your import. It will be complicated to overhaul the whole system. But there is an incentive to reduce emissions in the chain.

- European Due Diligence legislation. The European Commission will propose legislation this Summer on 2 issues the European Parliament adopted reports on: 1) in October 2020, it adopted recommendations on an EU legal framework to halt and reverse EU-driven global deforestation and 2) in March 2021, it adopted the legislative initiative report with recommendations on corporate due diligence and corporate accountability. The plan is to oblige importers to demonstrate that there is no deforestation in their chain (since, for example, 2015). Doing so, transparency provides insight in the chain emissions. This could give companies also the opportunity to invest in forest protection or forest protection credits (so-called REDD credits). There may also be a link with the forthcoming proposal for a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism in July, whereby the importer will incur the same CO2 costs as in the EU. The European Parliament would like the European Commission also to propose to charge EU companies on its own international chain emissions.

In short, there are enough options to make use of the flexibility, affordability, and international reach of international chains to tighten the climate target and to tackle 50% of the emissions.