At the recent Climate Summit in Baku, November 2024, world leaders took a bold step toward tackling the climate crisis. The summit gave the official green light for the use of carbon markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, a mechanism designed to help nations meet their climate commitments while mobilizing much-needed climate finance for the Global South. This milestone paves the way for innovative CO2 agreements that could soon become a cornerstone of global climate strategy. [This article appeared earlier on Qcintel ]

Sweden, a pioneer in climate action, showcased its leadership by signing bilateral carbon deals with with Zambia and Nepal. during the summit. The other countries Sweden has bilateral agreements with are Zambia, Ghana, Dominican Republic, Rwanda and Switzerland. Caroline Asserup, Acting Director General at the Swedish Energy Agency described the agreement with Zambia as “an important step towards establishing concrete climate projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, contribute to sustainable development and help raise climate ambition in both Sweden and Zambia”.

Under these agreements, Zambia can count part of the resulting emissions reductions toward its climate targets, while Sweden uses the remainder to exceed its already ambitious goals of a 63% reduction by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels) and achieving climate neutrality by 2045. Its target is also beyond its target with the EU [1]. A earlier CO2 deal with Switzerland is meant for example for Direct Air Capture projects, which are critical to meet the Swedish negative emissions target after 2045.

Sweden is the first EU country having Art 6.2. deals. At the Environment Council Meeting in December, Minister for Climate and the Environment Romina Pourmokhtari advocated that the EU should make use of Art 6 credits for its future CO2 targets.

How Article 6.2 Bilateral CO2 Trading Works

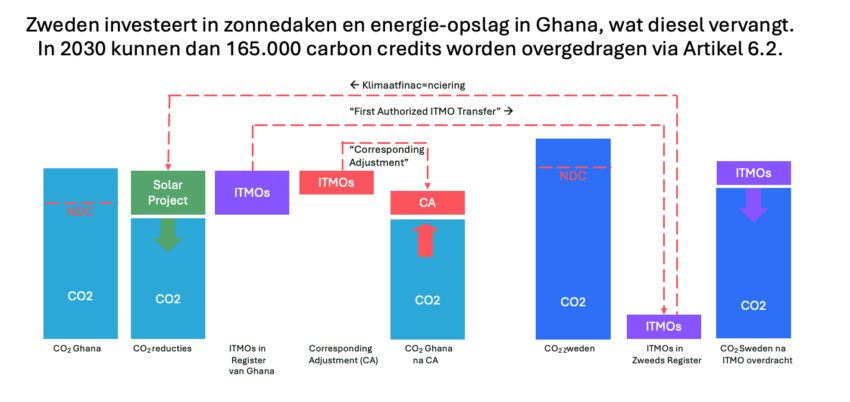

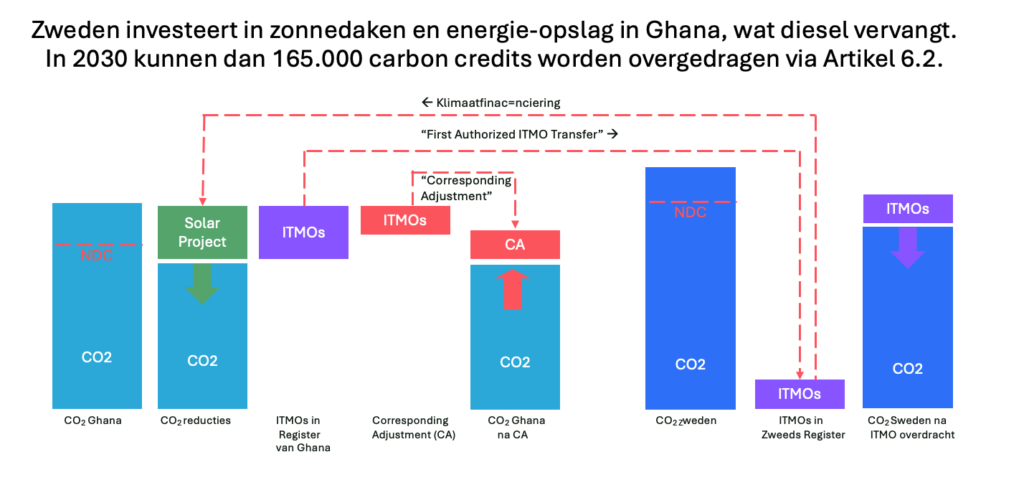

The crux of an Article 6.2. deal is “The use of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (IMTOs) to achieve nationally determined contributions”. And after credits have been transferred, the reduced or removed emissions are added back as emissions to the selling country’s inventory to avoid double countring: the so-called ‘corresponding adjustment’. See figure below how thart works. David Newell, Sweden’s negotiator for Article 6 said in Baku: “the agreed rules for transparent reporting, how to manage inconsistent reporting and the establishment of an international register provide the conditions for CO2 trade, compatible with the longterm Paris goals”.

Hence, it is up to each host country Sweden invests in to choose HOW it meets its own NDC. So, it is up to the two trading countries to define what the basis of its ITMO issuance into its Art 6.2. registry and transfer is. The mean eligibility requirement of Art 6.2. is: will the selling country meet its NDC? For the Art 6.2. investment it is important to disclose information on the type on the project, and the monitoring and reporting, to justify the use of public funding. To develop tools for the promotion of sustainable development Sweden cooperates with carbon credit issuer Gold Standard.

For example, the CO2 deal with Ghana on roof-mounted solar with energy storage (see figure above) includes sustainability goals too. And it describes that a ‘share of gross proceeds’ of ITMO transfer is reserved for adaptation and a share of ITMOs shall be cancelled and not used by Sweden, to contribute to the overall mitigation of global emissions. For the rest Art 6.2. is a very flexible climate cooperation mechanism, approved by the Paris Agreement.

Lessons from the Past: the new Art 6.4. Crediting Mechanism

Besides bilateral Art 6.2. deals, the new the “Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism” (PACM) aims to avoid the pitfalls of the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), which faced criticism for lax standards. Under Article 6.4—the centralized issuance system for less advanced climate policies—projects must meet stricter sustainability and emissions-reduction methodologies. While this approach ensures rigor, it also introduces additional layers of UN oversight according to Art 6.4., which some fear could slow progress. The issuance of the Art 6.4ER credits needs to meet agreed Art 6.4. carbon methodologies, to be developed, and the sustainability tool.

Transparency on Art 6.2. Deals is Key

The above Art 6.4. project based requirements are not valid for Art 6.2. deals. Hence, the Baku decision on Article 6.2 emphasizes transparency and accountability. However, the Baku Decision on Art 6.2. text also includes the request to submit detailed information on factors like ‘avoiding emissions lock-in, technologies inconsistent with achieving long-term goals and ensuring public participation’. While these project-based aspects are generally relevant for robust climate policy, applying them to every individual carbon transfer risks undermining the sovereignty of trading nations, public discussions with reputational repercussions and discouraging private investment for Art 6.

The Importance of Keeping It Simple

For example, a CO2 deal between Switzerland and Thailand, aimed at funding electric buses for Bangkok’s public transportation, faced criticism from a Swiss organisation claiming the emissions reductions were not “additional”. Yet, such debates are irrelevant under Article 6.2. What truly matters is the practical impact: improving Bangkok’s air quality and reducing 0.5 million tons of CO2 from 2022 to 2030 and corresponding adjustment, while meeting hist country’s NDC. Moreover, residents of Bangkok don’t need a bureaucratic debate to tell them the value of cleaner buses. They simply benefit from reduced pollution and better public health in Bangkok. This underscores the importance of avoiding overcomplication in carbon trading rules.

A Call to Action

Sweden’s proactive approach offers a compelling example of how CO2 agreements can deliver measurable climate benefits cost-effectively. By balancing flexibility with accountability, Article 6.2 has the potential to catalyze meaningful climate action worldwide. However, as we’ve seen with the Bangkok bus project, we must resist the urge to overcomplicate the system.

The world doesn’t have time for endless debates. The climate crisis demands action. Let’s embrace mechanisms like Article 6.2 with the urgency they deserve, ensuring they remain accessible, effective, and focused on real-world impact. Hop on the bus—and let’s drive toward a sustainable future.

[1] Swedens climate target with the EU is -55% in 2030 and climate neutrality in 2050